VIA – SANTA CRUZ SENTINEL

Family, law enforcement still fighting for peace two years after gang, surf cultures collide

By Cathy Kelly and Stephen Baxter

Posted: 10/15/2011 04:01:32 PM PDT

SANTA CRUZ — Two years have passed since surf and gang cultures collided with fatal results on a dark Santa Cruz street.

Neighborhood groups have formed to fight back against gang violence. Families continue to struggle with their loss, waiting for suspected killers to face justice. And police, educators and community leaders have worked tirelessly in hopes of stopping the violence.

Inside a Santa Cruz County Superior Court room, three of five men believed to have been involved in the Oct. 16, 2009, slaying of Tyler Tenorio have listened as nearly three weeks of testimony have played out in their preliminary hearing. Judge Paul Marigonda will determine whether the words of Tyler’s friends, detectives and forensic experts are enough to try the suspected Santa Cruz County gang members on murder and gang charges.

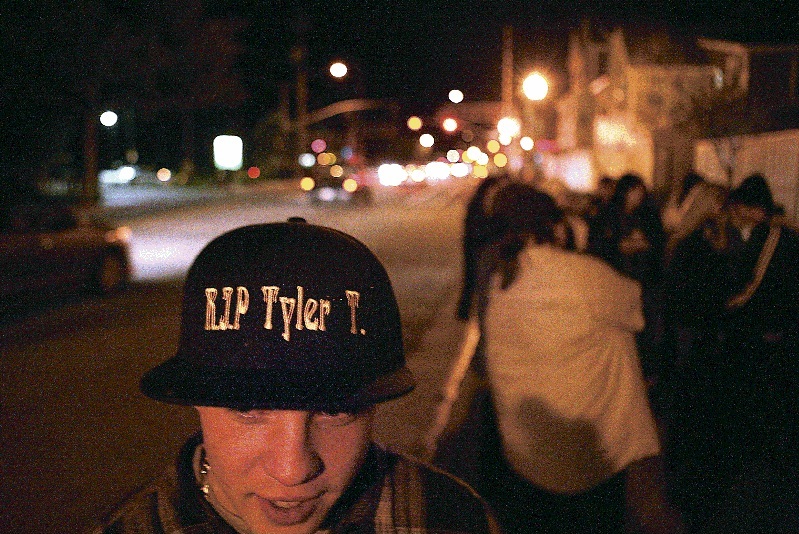

Andrew Tennyson, who was in the car with Tyler Tenorio the night he died, stands near the corner of Laurel and Chestnut streets, where Tyler was stabbed. (Robinson Kuntz/Sentinel file)

Tyler was stabbed at least 15 times on a dark residential street near downtown after what started as a normal night out with four friends. A bonfire at the beach was a bust, leaving the four young men and one teenage girl driving around town, idly passing time listening to hip-hop music.

But tension in the car and what seems to have been an innocent “Westside” shout-out to a couple of young men on the street quickly turned violent, forever changing the lives of teens from what one might call both sides of the tracks.

Tyler and his friends were skateboarders, Santa Cruz High students, all in their teens. The young men on the street corner were suspected Eastside Sureño gang members. The school’s colors, Cardinal red, and popular red surf gear colors, and the gang’s trademark blue might have contributed to the clash that night. That color red may have been mistaken for a rival gang. Or perhaps it was the word “Westside” that brought a quiet night to a tumultuous end.

“This town has had a surf rivalry for years, and it was a friendly rivalry. But now when people are exchanging words in the water it doesn’t just result in an argument or fist-fight,” Deputy Police Chief Rick Martinez said referring to the popular “Eastside”, “Westside” references. “Sadly, everyone is arming themselves with knives. We didn’t see that in the past.”

That night, Tyler wore jeans, a white shirt and a jacket, his mother said. His Nikes were white with a red swoosh — which Sureños could have interpreted as representing the Westside and Norteños, though it was dark and not likely to have sparked the fight.

Ashley Atkins, a friend and classmate, said Tyler sometimes wore red and the popular “Westside” surf logo from Arrow Surf Shop simply because he grew up there — not because he was in a gang.

“He was a skateboarder guy. We thought of the Westside as a place we hung out,” she said. “We didn’t think of it as a gang term.”

No one is sure what caused the bloodshed that night. But its consequences forever marked the sleepy beach town.

Of a dozen or so students interviewed outside the high school last week, all knew about Tyler.

“It has definitely brought more awareness,” senior Robert Schultz said. “There are certain places you just know not to go at night anymore. There is still some tension at school, between some Latinos and others, but not as much as when I was a freshman.”

That tension, said Schultz and fellow senior Anthony LaFrance, comes most from looks, or “muggin’ ” as LaFrance called it.

neighborhood, a surf spot, a gang and a popular term thrown around by many young people in town. That night, police say, the way the car full of kids acted might have been interpreted as a gang challenge.

Police and others say gang-related violence in the city has calmed in the past two years, though they stop short of attributing that to a specific factor.

Without a doubt, the death of Tyler, 16, in October and the shooting death six months later of Carl Reimer, 19, caused a groundswell of sadness, outrage and calls for change throughout the city, dragging the gang problem into the forefront of mainstream society.

On April 23, 2010, Reimer, a Santa Cruz High School graduate and surfer, was gunned down at a Grandview Street apartment complex near Mission and Swift streets. No one has been arrested in his slaying.

Tyler was a junior at Santa Cruz High and a friend of Reimer. Two of Tyler’s suspected killers also have not been arrested. Neither Reimer nor Tenorio were gang members, police say.

Born out of the tragedies were several community movements, chief among them a grass-roots crime-prevention group called Take Back Santa Cruz. The fateful events boosted the ranks of Santa Cruz Neighbors and sparked the formation of a Santa Cruz High student association called Peace in the Streets.

THE CASE

Back in court, the three accused suspects have appeared nearly daily since the Sept. 27 start of a preliminary hearing that will determine whether prosecutors have enough evidence to hold them pending trial.

Those men are Walter Escalante, 25, of Watsonville, Daniel Onesto, 21, of Santa Cruz, and Pasqual Reyes, 22, of Live Oak. Paulo Luna, 23, is believed to have fled to Mexico, and Ivan Ramirez, 23, of Capitola, remains outstanding as well.

For Penny Tenorio, Tyler’s mother, the courtroom is the hardest place for her to be. On Tyler’s Facebook page recently, she thanked “everyone for being here for my Ty and his fam.”

But Penny said she can’t bring herself to attend the hearing; reading and listening to details of what happened to her son, she said, “rips my heart out even more.”

In an interview last week, Penny said she occasionally writes how much she misses Tyler on his Facebook wall. Her pain is evident in her words.

She welcomes visits from Tyler’s friends who stop by her Westside home. Some she knows better now than before her son’s death, she says.

She insists Tyler “was a kid. He wasn’t a fighter. It’s been almost two years and it’s like it was yesterday.”

FATEFUL NIGHT

On that Friday night, Tyler was in the back seat of a Mitsubishi Gallant when his friend and the car’s driver, Angel Palacios, yelled “Westside!” to two men who stared at him on the street corner.

“I don’t know, it was just something I blurted out. I was mad at the time,” Palacios testified in court last month.

The pair on the street responded throwing rival gang signs, Palacios said, admitting he accepted the challenge when he jumped out, leaving the engine running, his girlfriend in the front seat. He and the rest of the boys confronted what turned out to be “armed” men.

Witnesses said the two men called out six or more from a nearby apartment complex — known as Sureño gang territory.

The boys were outnumbered, unarmed and certainly not prepared for what unfolded.

When Palacios thought one of the men had a gun, he told his buddies to run.

They did, but the aggressors tripped Tyler as he fled. The men kicked, punched and beat him, finally stabbing in the stomach and back more than 15 times.

Seamus Wilson, one of the boys in the car, realized Tyler hadn’t made it out. He went back and dragged Tyler away, even as the men kicked and beat him about the head.

Sirens likely scared the attackers, who fled into the darkness, leaving Tyler and Seamus huddled on the street. Tyler died in his friend’s arms despite help from an off-duty lifeguard who was there almost immediately and the first-responders who were just moments behind.

The three others left Seamus to walk home alone into the darkness of the night, the suspects on the loose.

While none of Tyler’s friends can positively identify any of the three men in court, police says fingerprints lifted from beer cans found near the scene match some of the defendants.

EASTSIDE/WESTSIDE

For Tyler’s friends, life goes on.

Santa Cruz High sophomore Anna Chavez said students continue to use the terms “Westside” and “Eastside,” which for decades simply identified neighborhoods or surf spots.

But the words have deeper meaning.

“Eastside/Westside is more of a popularity thing, but I also know it has gotten kids killed — not for being in a gang, but for acting like they are or thinking that is cool,” Chavez said. “They still, in photos, will throw (signs denoting) ‘Westside’ or ‘Eastside,’ but that can get them in trouble later if they are in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Darryl “Flea” Virostko, a well-known Westside surfer, said he often sees teens clad in red and always warns them.

“When I see kids wearing a red hat and red shirt, the kids are 13- to 17-years-old. They don’t really know what they want to be,” said Virostko, the big-wave surfer and star of “The Westsiders”, a documentary film chronicling his difficult upbringing and addiction to drugs.

“I definitely try to wake kids up and say, ‘Hey, you’re going to get shot. You gotta lay a little bit low.’

“You’re proud of where you’re from, but it goes to a certain point,” said Virostko, now 39.

Martinez, the deputy police chief, says violence in the city subsided a bit this summer, something he hopes is the result of the gang prevention work police, educators and others do.

“Our hope is that the Tyler Tenorio and Carl Reimer cases really hit home the point we have been trying to make. That culturally you should really know what you are getting into if you represent yourself as an ‘Eastsider’ or ‘Westsider’,” Martinez said.

Kids need to think about why they’re accepting that challenge and what it means, he said.

“Are you just young and full of testosterone or are you representing a prison gang?”

MOVING ON

The Tenorio and Reimer slayings led Santa Cruz police to establish partnerships with federal agencies to combat gang violence. Pressure from city residents spurred the City Council to approve filling eight vacant police officer positions. Police launched a gang-prevention program called PRIDE at the city’s two middle schools.

Last month, every law enforcement agency in the county united to form a countywide gang task force.

Last year, educators formed the North County Broad-based Apprehension, Suppression, Treatment and Alternatives program. Known as BASTA, it links leaders in education, law enforcement, government, the judicial system, counseling, probation and other fields to keep teens in school and out of gangs.

The group is holding a parent education meeting open to all at 6 p.m. Wednesday at Mission Hill Middle School to provide information on how to keep teens safe from gangs and other dangerous influences.

This week, the county Office of Education’s student services division manager, Michael Paynter, said an arm of BASTA has begun accepting referrals of at-risk students from schools, law enforcement officers and others and getting them assistance that includes relationships with mentors that the students help choose.

“They just have to be willing to talk and receive some kind of assistance,” Paynter said.

WORKING WITH GANGS

Barrios Unidos outreach worker David Beaudry, a former Los Angeles gang member and songwriter, has been working with gang members on the Westside since Tyler’s death.

Some of Beaudry’s work is done at Circle Church, where Tyler used to skateboard. Beaudry said he has contacts in the Chestnut Street area, near the scene of the crime, as well. Beaudry establishes relationships with gang members, finding employers who will mentor young people as a way to stem gang violence.

“I think Tyler’s death got a lot of the younger kids to start rethinking what they were headed into,” he said. “And then with Carl it was like the exclamation point, it changed a lot. I’ve seen a lot of younger kids that were fairly deep sort of drift away and get back to a quieter life.”

Beaudry agrees gang activity has quieted, party because of police efforts, but it hasn’t gone away, just underground.

“They are inside houses more and playing it more low-key,” Beaudry said. “But it’s still in place and there still needs to be a lot of work there.”

TEEN EDUCATION

Jenny Emberley, a 16-year-old Santa Cruz High senior, said the loss of Tyler and Carl led to less denial by teens of the dangers of gangs.

For the full article go here:

http://www.santacruzsentinel.com/ci_19119034?source=most_viewed

Become A Sponsor!

Become A Sponsor!If you have a product or service that is a good fit for our surf community, we have opportunities for you to sponsor this blog! Download our media kit now!