VIA – NY TIMES

With Powerboat and Forklift, a Sacred Whale Hunt Endures

Photo: After a hunt, a whale was quickly carved up and divided into shares. More Photos »

By WILLIAM YARDLEY and ERIK OLSEN

Published: October 16, 2011

BARROW, Alaska — The ancient whale hunt here is not so ancient anymore.

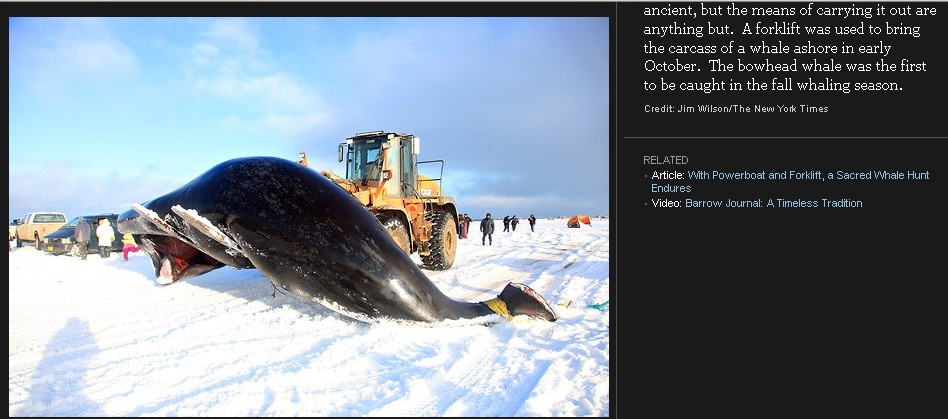

“Ah, the traditional loader,” one man mumbled irreverently. “Ah, the traditional forklift.”

That morning, the first of the annual fall hunt, a crew of Inupiat Eskimos cruising the Arctic Ocean in a small powerboat spotted the whale’s spout, speeded to the animal’s side and killed the whale with an exploding harpoon. By lunchtime, children were tossing rocks at the animal’s blowhole while its limp body swayed in the shore break like so much seaweed. Blood seeped through its baleen as a bulldozer dragged all 28 feet of it across the rocky beach. At one point, one man, not Inupiat, posed beside the whale holding a small fishing rod, pretending for a camera that he had caught it on eight-pound line.

Eventually the heavy equipment gets the job done, and the whale is lowered onto the snow — and the shared joy is obvious. Big blades emerge and the carving commences. Steam rises when the innards meet the Arctic cold. Within an hour, nice women are offering strangers boiled muktuk — whale meat. People mingle. “Congratulations,” they tell the family of the crew.

A young man bends over the liver and peels off the membrane so he can take it home to make a traditional drum. A row of Eskimo children slide on the slippery skull bone. A biologist reaches into the whale’s eye sockets, making sure someone remembered to cut out its eyeballs so the lenses could be used to determine its age.

When a second whale is landed that evening, the middle-aged captain whose crew killed it, a descendant of men who have hunted whales here for thousands of years (subtract the outboard motors, the Caterpillar D7H and the Carhartt foul-weather gear), climbs the sea mammal in waterproof boots and bibs, raises his arms to the people who are sending celebratory text messages and shining the headlights of their extended-cab trucks on the scene, and says “Ah ah ha!”

The crowd repeats this back to him: “Ah ah ha!”

Again, the muktuk is carved. Again, a biologist cuts out an eyeball. Asked whether this is a good place to pursue his work, Hans Thewissen, a whale expert who travels here regularly from his job at Northeastern Ohio Universities Colleges of Medicine and Pharmacy, said, “This is the only place.”

The captains will open their houses over the next few days, distributing muktuk to the community, not so differently from the way their ancestors did. Before Arctic Alaska began being pulled into the developed world in the 19th century, before Pepe’s North of the Border, a Mexican restaurant, opened in Barrow in 1978, before Oscar Mayer Lunchables reached the impulse aisles at the big-box store next to the museum, bowheads provided the central food, energy and spiritual sustenance for Eskimo villages. Families used the whales’ bones to frame sod houses and mark the graves of the dead.

The federal government and the International Whaling Commission allow the whale hunt to continue, under tight control, as a subsistence tradition. Bowheads, which number about 11,000, are an endangered species, though the population is increasing. Alaska Eskimos harvest less than 1 percent of them each year.

This year, Barrow’s quota, the largest given to Alaska’s whale-hunting villages, is 22 strikes, including the 9 by Barrow hunters as the animals migrated to summer feeding areas in the Beaufort Sea this spring. Many hunters use more traditional methods in the spring, traveling across sea ice and paddling toward whales in sealskin boats. In the fall, the whales make their way west and south before the winter ice arrives.

“Fall whaling is for lazy whalers,” said Eugene Brower, head of the Barrow Whaling Captains Association, ribbing more than criticizing his fellow hunters.

Experienced whalers say a combination of factors, including that relative ease and ice thinning in spring from climate change, have made the fall hunt more prominent. This year, it started on Oct. 8, the latest in memory.

Mr. Brower is the grandson of Charles Brower, a white man who arrived in the Arctic on a commercial whaling ship in the 1880s, married an Inupiat woman and stayed. Mr. Brower, the grandson, still uses a heavy brass harpoon gun stamped as having been made in a very different whaling capital, New Bedford, Mass., in 1878.

Here in Barrow, the snowy flats by the beach where the whales are butchered (the snow covers an old runway used by the former Naval Arctic Research Laboratory) are splashed with patches of blood and guts until more snow falls. Some blubber ends up in the trash, no longer prized as fuel for heat and light when a drill rig nearby makes natural gas cheap and easy.

The whale hunters know what some people think of all of this, and many are wary when news crews show up with cameras. They know what the animal-rights people will say — and insist they will misunderstand.

“We’ll never stop doing this,” Fenton Rexford, a candidate for mayor of the North Slope Borough, the northernmost municipality in the United States, said as he watched the festivities. “No one can stop what our fathers and forefathers have done for thousands of years. But we’re highly adaptable people. We use what tools are available to us to make life easier.”

For the full article go here:

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/17/us/in-sacred-whale-hunt-eskimos-use-modern-tools.html

Become A Sponsor!

Become A Sponsor!If you have a product or service that is a good fit for our surf community, we have opportunities for you to sponsor this blog! Download our media kit now!